The introduction of a new fish to a home aquarium is a moment filled with anticipation, yet it is also fraught with an invisible peril: osmotic shock. This acute physiological distress is the single most significant danger a new aquatic pet faces, arising when it is transferred too rapidly between waters with differing chemical makeups. Understanding and mitigating this threat through patient, methodical acclimation is a cornerstone of responsible fishkeeping.

The phenomenon is governed by osmosis, the fundamental physical process where water migrates across a semi-permeable membrane, moving from a region of lower solute density to one of higher density. A fish’s skin and, more importantly, its gills, function as such membranes. Their bodies are in a constant state of osmoregulation, a high-energy process of maintaining a stable internal equilibrium of water and dissolved salts. A sudden shift in the external environment can overwhelm this delicate biological machinery, leading to catastrophic cellular failure.

Mastering this aspect of aquatic biology is essential for creating a thriving underwater ecosystem. It is a lesson in the critical importance of environmental stability. This same principle of replicating precise chemical conditions to support life is also fundamental to advanced aquascaping, such as the creation of a specialized blackwater biotope, where specific water parameters are painstakingly recreated.

The Cellular Pressure Cooker

To comprehend the severity of osmotic shock, one must visualize its effects at the microscopic level. The cells within a fish’s body maintain a specific internal concentration of salts and minerals. The fish’s osmoregulatory system, driven by its kidneys and specialized cells in the gills, works ceaselessly to keep this internal environment constant, actively pumping ions and water in or out to counteract the surrounding water’s chemistry.

When a freshwater fish is abruptly moved into water with a higher concentration of dissolved solids (harder water), the process of osmosis forces water out of its cells and into the environment. This cellular dehydration causes the cells to shrink and shrivel, a process known as crenation, which leads to severe organ dysfunction. This is a state of hypertonic environmental stress.

Conversely, if a fish is transferred to water that is substantially purer or “softer” than its previous environment, the opposite occurs. Water from the outside floods into the fish’s cells in an attempt to equalize the concentration gradient. This influx causes the cells to swell and, in extreme cases, to rupture and die, a process called cytolysis. Both forms of osmotic shock can be lethal if the environmental change is too sudden.

The Drip Acclimation Protocol

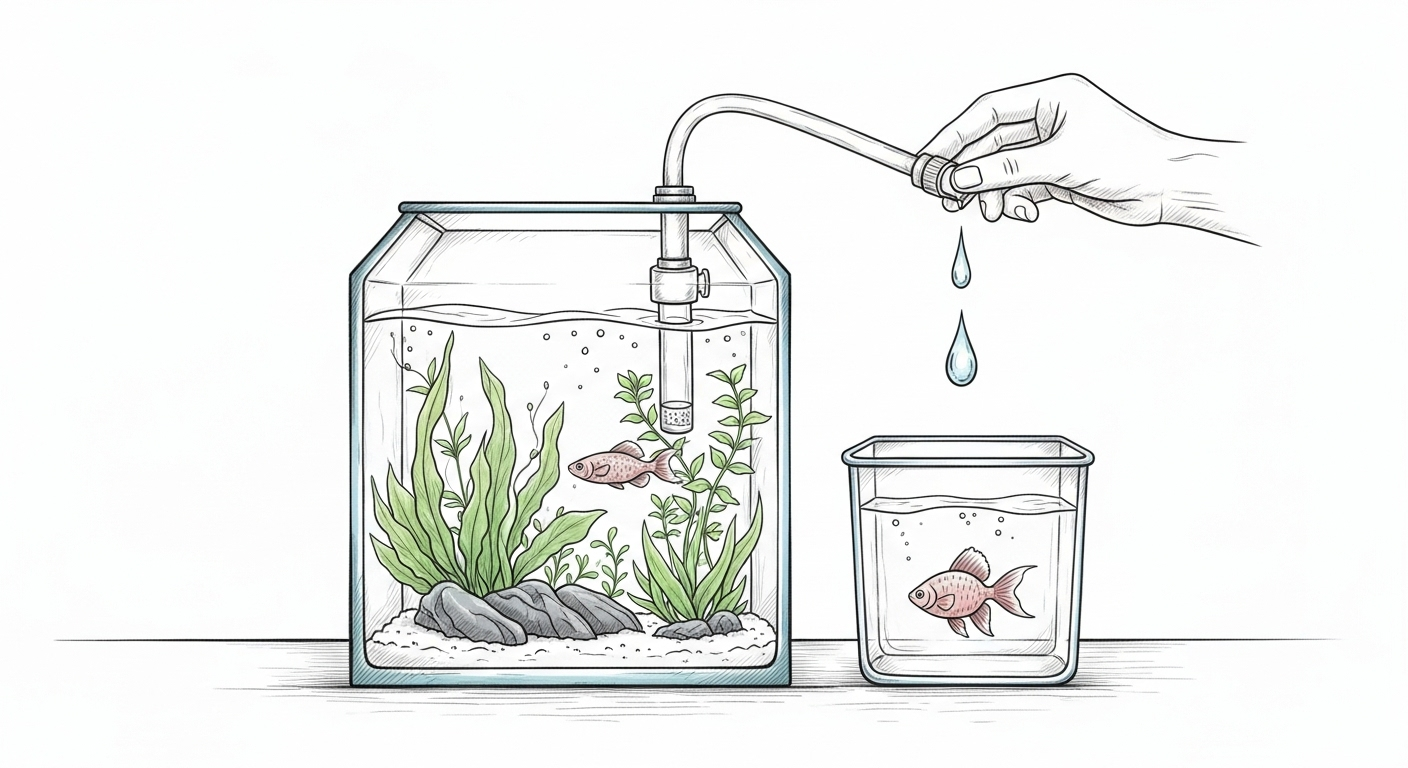

The most reliable and humane method for preventing osmotic shock is drip acclimation. This technique facilitates a slow, gradual equalization of the water chemistry, giving the fish’s metabolic systems ample time to adjust without being pushed into a state of crisis. The procedure is simple and requires only a bucket and a short length of airline tubing.

The protocol involves a deliberate, patient series of steps to ensure a stress-free transition for the new inhabitant.

- Initial Setup: The fish is gently placed, along with all the water from its transport bag, into a clean, dedicated bucket.

- Siphon Start: The airline tubing is used to start a siphon from the main aquarium into the acclimation bucket. A simple knot tied in the tube can serve as a valve to regulate the flow.

- The Gradual Drip: The flow rate is adjusted to a slow, consistent drip, ideally between two and four drips per second. This slowly introduces the new water chemistry to the fish.

- Dilution and Transfer: Over a period of at least one hour, the water volume in the bucket will have doubled or tripled. At this point, the fish is fully accustomed to the new parameters and can be carefully netted and moved to its new home.

This patient approach is considered the professional standard for introducing any sensitive or high-value aquatic life, as it minimizes stress and maximizes the chance of survival.

pH and the Compounding Stress Factor

While differences in salinity and mineral content are the direct cause of osmotic pressure, a rapid swing in pH can act as a powerful compounding stressor. The pH scale measures the acidity of the water, and a fish’s entire biochemistry, including enzyme function and its ability to absorb oxygen through its gills, is calibrated to operate within a narrow pH range. A sudden change can severely disrupt these vital processes.

An acute stress response triggered by a pH shock can significantly hinder a fish’s ability to osmoregulate properly. This impairment makes it even more susceptible to the cellular damage caused by osmotic pressure. Thus, the drip acclimation method serves a dual purpose: it matches the water hardness and also allows the fish’s body to gradually buffer and adapt to the new pH level.

This is why testing the pH of both the store’s water and your own tank is a critical preliminary step. If there is a substantial difference (generally more than 0.5 points), a slow drip acclimation process is not merely advisable; it is mandatory for the well-being of the animal.

Recognizing the Signs of Distress

Identifying the symptoms of osmotic stress is a crucial skill for an aquarist, although by the time these signs become apparent, the internal damage may be irreversible. A fish undergoing osmotic shock will display unambiguous signs of severe distress. These symptoms can include extreme lethargy, frantic gasping at the water’s surface, erratic or spastic swimming, and fins clamped tightly against its body.

In advanced stages, the fish may lose its ability to maintain its position in the water column, often listing to one side or floating inverted. These are indicators of severe neurological and organ failure resulting from widespread cellular damage. The only responsible course of action is the proactive prevention of shock through a proper acclimation procedure.

This underscores the fundamental duty of care inherent in fishkeeping. As aquarists, we assume responsibility for the lives we bring into our homes, and that responsibility begins with providing a biologically safe and stable environment. A few extra minutes or hours of patience during acclimation is the first and most profound expression of that commitment.

Frequently Asked Questions

While hardy fish can sometimes survive a less careful introduction, it is still a highly stressful experience for them. Drip acclimation is always the kindest and safest method, even for a tough fish. For delicate invertebrates like shrimp, which are extremely sensitive to changes in water parameters, it is absolutely essential.

An absolute minimum for any fish should be 60 minutes. For more delicate species, such as saltwater fish, discus, or sensitive invertebrates, a longer period of 90 minutes to two hours is highly recommended to provide the most gentle and stress-free transition possible.

Before starting the drip acclimation, you should float the sealed bag in your aquarium for 15-20 minutes. This allows the temperature of the water in the bag to slowly equalize with the temperature of your tank water. Temperature shock is another stressor that should be avoided, and this simple step addresses it before you begin the chemical acclimation.